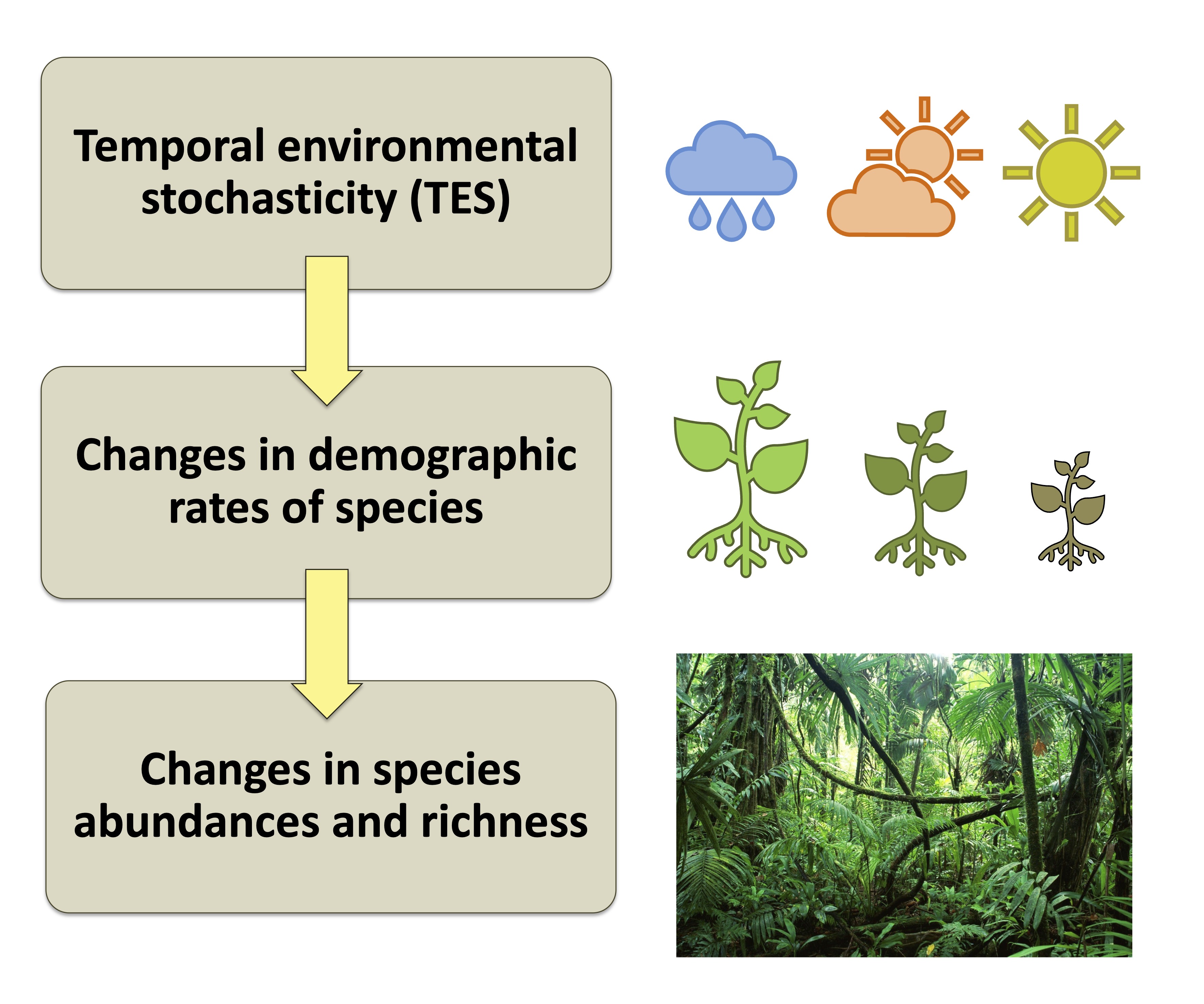

The ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus espoused that life is continuously in a state of flux, and this is attested by the ubiquity of temporal changes in environmental conditions such as precipitation and temperature, which are often well characterised by a random process and referred to as temporal environmental stochasticity (TES). TES results in random changes in species’ demographic rates over time, with profound cascading effects on community dynamics and species richness. This is the topic of a new review paper published in Mathematical Biosciences, authored by Tak and Ryan in collaboration with colleagues Jayant Pande from FLAME University, Nadav Shnerb from Bar-Ilan University and James O’Dwyer from the University of Illinois.

In our review, we synthesise studies that have analysed process-based community models to quantitatively examine how TES affects species richness. The simplest community models assume that species interactions are so weak that they can be ignored, such that community dynamics are essentially the sum of independent species dynamics, thus being amenable to mathematical analysis. More complex community models incorporate non-negligible interspecific interactions, which renders them more difficult to analyse. However, techniques from “mean-field theory” can be used to represent the strengths of interspecific interactions as time-averaged constants, such that community dynamics can be represented effectively as the sum of independent species dynamics and analysed.

Our review identified important processes via which TES affects species richness. Firstly, TES increases temporal fluctuations of species populations, such that the variance in species abundance over a particular time period scales quadratically with the initial abundance, in contrast to the linear scaling found in the absence of TES. The greater TES-induced fluctuations tend to promote species extinctions by bringing the abundances of species more frequently to the extinction threshold, thus decreasing species richness. Secondly, in competitive communities, non-linear averaging of TES-induced temporal fluctuations in interspecific competition strength (via Jensen’s inequality) can result in weaker interspecific competition on average, thus increasing species richness. However, this effect only dominates when the temporal correlation of environmental conditions is sufficiently short. If the correlation is too long, then this allows strong selection of the fittest species between infrequent changes in environmental conditions, which decreases species richness.

We end our review by discussing fruitful avenues for further research. These include a greater focus on interspecific interactions other than competition, for example consumption and mutualism. They also include examining eco-evolutionary feedbacks that critically shape the response of a species to TES, which may mitigate the effects of TES. Furthermore, there is much scope to explore how TES affects species richness in spatially explicit settings. Successful exploration of these new avenues requires development of new theory, collection of more community data, and better integration between theory and data.